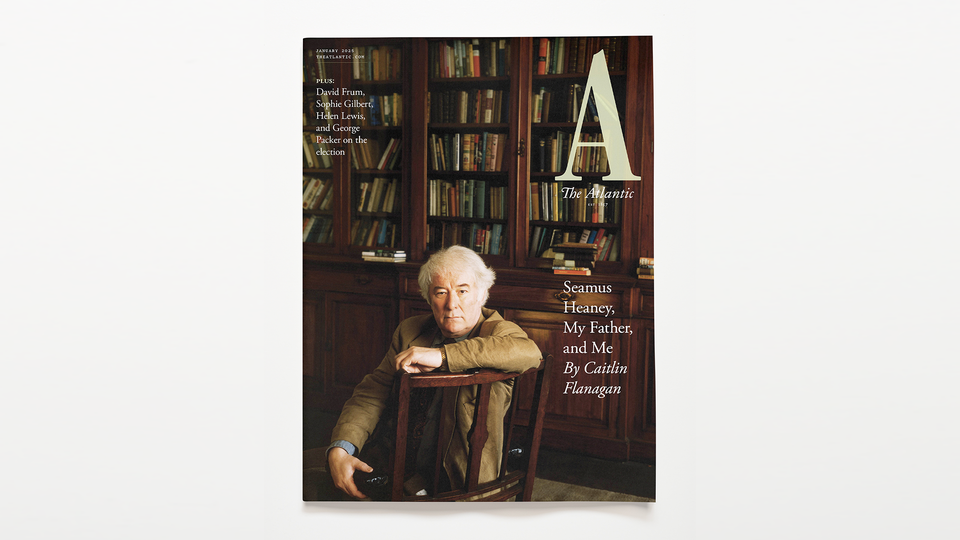

For The Atlantic’s January cowl story, “Stroll on Air Towards Your Higher Judgment,” employees author Caitlin Flanagan writes for the primary time about rising up with the Nobel Prize–profitable Irish poet Seamus Heaney, and what her household’s shut friendship with the Heaney household supplied her. She writes: “Seamus gave me the one factor I desperately wanted rising up in that loopy household: my certificates of belonging.”

In 1970, Heaney arrived in California along with his household to spend the educational 12 months within the UC Berkeley English division, the place Caitlin’s father, Tom, was a professor. Caitlin’s dad and mom have been virtually 20 years older than the Heaneys, and took the visiting household underneath their wing. “Berkeley swings like a swing-boat, has all the color of the fairground and as a lot incense burning as a excessive altar within the Vatican,” Heaney wrote to his editor shortly after arriving. The next 12 months the Heaneys have been again in Eire, and so have been the Flanagans, for Tom’s sabbatical.

Lengthy earlier than his Nobel Prize in Literature and worldwide acclaim, Heaney was a household buddy to the Flanagans and a second father to Caitlin. Heaney typically in contrast his bond with Tom as one between father and son: “I supposed you’re destined to be a father-figure of kinds to me,” he wrote to Tom in 1974. “Blooming terrible.” Caitlin babysat the Heaney kids; as soon as, Heaney constructed the Flanagans a bookcase. A long time later, Heaney would write Tom’s obituary for The New York Evaluation of Books.

The households have been so shut that on the event of Caitlin and her sister’s baptisms into the Catholic Church in 1971, Heaney wrote the ladies a poem. Caitlin writes, “When Seamus stood up and browse the poem, ‘Baptism: for Ellen and Kate Flanagan,’ I accepted every thing—all of it, unexpectedly: poetry, God, and myself. For half a century, I’ve saved the piece of onionskin he typed that poem on, so skinny that it’s virtually translucent. It’s a blessing on the lengthy, unusual venture of being Kate Flanagan.” (The poem is being printed for the primary time, alongside the quilt story.)

Within the cowl story, Caitlin explores Heaney as an individual and poet, and the extraordinary affect that he and his spouse, Marie, had on her. Caitlin writes: “He had a way of obligation to others that in anybody else can be incapacitating. As soon as, when my very own kids have been small, I took them to go to Seamus and Marie. After tea and hugs, we climbed into the taxi, and the motive force mentioned, ‘So that you’ve been to see the nice man.’ Virtually across the nook was a billboard along with his image on it, selling a brand new documentary. By his later years, there was no escaping himself, and the limitless duties the function entailed. He might have fantasized about ditching these duties, however he by no means shirked them.”

In writing about Heaney, Caitlin can be writing about relationships, kindness, and the indelible impression the individuals we love go away on our lives. A number of months in the past, Caitlin made her first go to to Heaney’s grave in Eire, a full decade after he died. She writes of the go to: “We are able to’t escape it: shedding the individuals we love and wish essentially the most. Every dying must be countenanced as a truth, squared away within the report books. However there are individuals so well-known to us, so cherished, that dying is another factor that may be turned to air.”

Caitlin Flanagan’s “Stroll on Air Towards Your Higher Judgment” was printed at the moment at TheAtlantic.com. Please attain out with any questions or requests to interview Caitlin on her writing.

Press Contacts:

Anna Bross and Paul Jackson | The Atlantic

[email protected]